Prindex is the first global comparison of perceptions of tenure security. By the end of 2019, we will have expanded our dataset from 33 to 140 countries, representing 95% of the world’s population. Measuring perceptions globally presents methodological questions and challenges. To clarify why we adopted our approach, this briefing, by Prindex researcher Joseph Feyertag, presents a review of the academic literature on perceptions of tenure security. Our findings contextualize the Prindex initiative, and help explain the choices we have made in order to be as reliable and accurate as possible within a national comparative framework.

In June 2019 we conducted a review of academic literature that uses the term “perceived” or “perceptions” in conjunction with “tenure security” or “secure tenure”. We limited the review to the 33 countries covered by the baseline Prindex survey in 2018. The aim is to benchmark the Prindex findings against existing quantitative evidence of perceived tenure security[1].

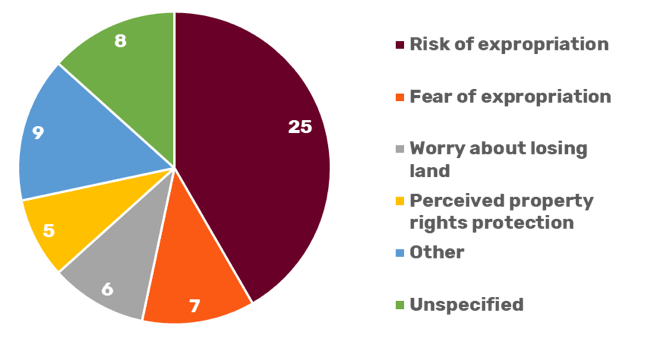

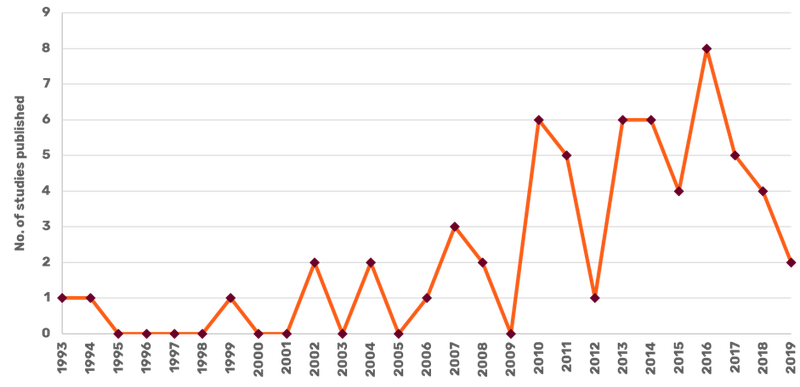

The search threw up over 1,650 articles and book chapters, of which 60 contained concrete quantitative evidence of rates of perceived tenure security or insecurity (Figure 1). Comparing this evidence to our results showed that, in practice, in few cases is the data comparable, due to the use of different sampling techniques and methodologies. The difficulties faced when comparing people’s perceptions are well documented by behavioural scientists and economists. In this brief, we summarise those issues by drawing on Prindex pilots and the evidence review, explaining that perceptions vary depending on i) how people are surveyed; ii) who is asked, and; iii) when they are questioned.

Table 1: Number of existing studies on perceived tenure security by country

How?

We considered two main factors when assessing how survey respondents are asked about their perceived tenure security. The first is the type of question used. Although almost every study uses a unique phrasing, we managed to categorise the questions into five groups:

1) Risk of expropriation: these are questions that ask respondents to consider their risk of losing land over a given time frame. For instance, Prindex asks respondents to assess the likelihood of losing land over the next five years;

2) Worry of expropriation: many questions in this category consider whether people would be worried if they left their land unattended or fallowed;

3) Fear of expropriation: these are questions about whether respondents are afraid or concerned about their land being expropriated;

4) Perceived property rights protection: questions relating to the perception of whether a respondent or a particular household member has the right to, for instance, bequeath, sell or rent land and/or property;

5) Other: in this category we have included a range of questions that cannot be categorised, mainly because they do not give enough information on the survey methodology or because they are the only study to use a certain question.

Unsurprisingly, the results in the evidence review vary considerably depending on the type of question asked. For instance, Stickler et al. (2018) find that 28% of respondents “fear encroachment by neighbours”, compared to 43% of respondents in the Prindex survey who consider it likely or very likely[2]. This is not altogether surprising and it is widely acknowledged that, for instance, a slum dweller or somebody in rented accommodation might consider it very likely that they will be expropriated over the next five years, but would not necessarily be worried about it (see e.g. Van Gelder, 2009: 131).

The Prindex methodology relies on a question relating to the “risk of expropriation”. As Figure 1 shows, this is also the most widely used single question among existing surveys of perceived tenure security. Two fundamental advantages underpin this popularity. Firstly, risk can be considered a better predictor of economic behaviour than worry or fear. People are more likely to act on a rational perception than an emotional assessment, although both are undoubtedly important. Secondly, when it comes to a comparative, international measure of perceived tenure security, risk perceptions are more consistent across languages and cultures than emotional assessments are. While people’s fears or worries can be expressed in multiple and sometimes complex ways across different cultures, what is considered “likely” or “unlikely” is more consistent[3].

Figure 1: Number of studies by type of question

A second consideration to take into account when asking people about their perceived tenure security are the answers offered to the survey respondent. This is more nuanced than differences in the type of question asked, but just as important. A question can be open-ended (e.g. in more qualitative studies) but in the vast majority of cases, existing studies offer a scale of options. These could be binary, such as “yes” or “no”, “likely” or “unlikely”, and so on. They can also have many more options, although scaling with an uneven number of options (e.g. 3 or 5) generally represent a Likert scale in which the middle response is neutral (e.g. “neither likely nor unlikely”).

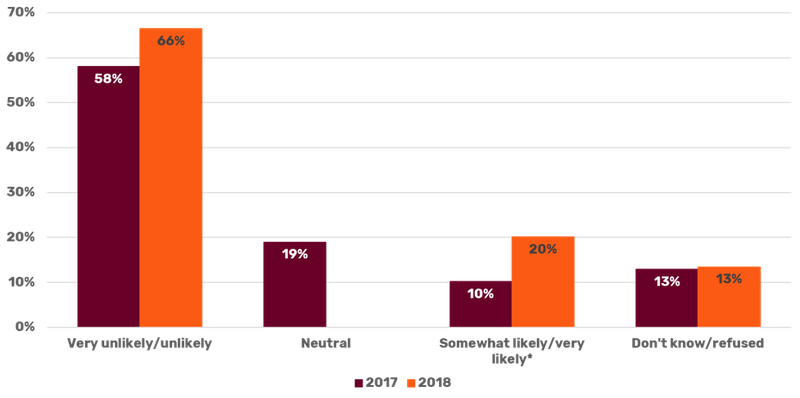

This may all sound trivial, but the importance of whether you use, say, a 4- or a 5-point scale can make a considerable difference to the results. Take Tanzania as an example. In 2017, Prindex ran a nationally representative pilot survey with a 5-point risk expropriation question, revealing that 58% of respondents were secure (“very unlikely” or “unlikely”), 10% were insecure (“likely” or “very likely”) and 19% said it was “neither likely nor unlikely” that they would lose their property in the next five years. When the survey was repeated in 2018 with the same sample size but using a 4-point scale, the results had shifted to 66% secure and 20% insecure (Figure 2). Evidently, respondents who had previously answered that it was neither likely nor unlikely, were now considering it “somewhat likely” or “unlikely”.

Figure 2: Comparison of 2017 and 2018 surveys in Tanzania using 4- and 5-point scale

*In 2017, respondents were given a choice of likely/very likely while in 2018, the responses were phrased somewhat likely/very likely.

Most of the studies in the evidence review, however, did not take such nuances into account. A majority do not report scaling (in which case we have assumed a binary yes/no scale) and when they do, results are very rarely reported as a share of total survey responses, including missing values (e.g. people who did not know or refused to answer the question). For the purposes of transparency, Prindex always reports results as a share of respondents who are secure, insecure and those who do not know or refuse to answer the question.

Who?

As much as perceptions are influenced by the way a question is asked, they are equally sensitive to who is surveyed. Feelings, emotions and value judgements may vary by gender, socioeconomic status, living arrangements, location or age, which is why Prindex methodology chose to consider a full spectrum of adult respondents aged 18 or above. This is done by asking a nationally representative sample in each country based on the latest census data.

The review shows that most existing evidence is concentrated in a particular region or sub-population. Many studies only consider smallholder farmers in rural areas (e.g. Deininger et al., 2019 in Malawi), or untitled households in informal urban settlements (e.g. Reerink and van Gelder, 2010). Other studies do not even measure data at household level, instead reporting perceived tenure security among businesses, villages or a plot level (e.g. Ayamga et al., 2015 in Ghana). There are also more subtle differences in the sample, such as when studies only consider land owners rather than renters or people who stay with or without permission (e.g. Deininger et al., forthcoming). While each of these approaches has relevance for the specific group studies, and in-depth surveys among certain groups should be supported, the evidence is as comparable as apples and oranges for inferences across countries. Only a consistent sampling design across countries can ensure comparability.

The further advantage of using a nationally representative sample is that it enables users of Prindex data to identify groups that are particularly prone to tenure insecurity. Based on this information, the data can encourage further, in-depth research that explores the issues that those particular groups face. For instance, 2018 Prindex data shows that women are particularly affected by insecurity in Peru, where further analysis revealed this to be especially the case for female respondents who “stay with permission”. Contrasting this, men were more insecure than women in Jordan. We can observe similar 'hot spots' if we look at other variables. In Niger, rural dwellers are particularly prone to tenure insecurity, while in next door Burkina Faso, the data shows urban dwellers suffer greater insecurity. A comparable, international survey therefore helps us to identify where help in securing people’s tenure is most needed.

Finally, to our knowledge, this is the first study of perceived tenure security that accurately represents the feelings of women. The Prindex sampling strategy does not interview the head of household or the most knowledgeable person, but uses a randomisation process to select a household adult for interview. Most existing surveys, even national household surveys, are overly skewed towards the views of men, who tend to be household heads.

When?

The third and final consideration that needs to be made when collecting data on people’s perceptions is the timing. People’s perceived tenure security can change from one moment to the next, depending on a wide range of social, political and economic developments. The announcement of a nearby infrastructure project, the results of an election, rumours of a private investment or a simply a quarrel with a neighbour can dramatically affect perceptions of tenure security. Unsurprisingly, therefore, surveys that were carried out years or even months apart are often not directly comparable.

Table 1 already revealed that in seven of the 33 countries reviewed no previous evidence of perceived tenure security exists. In other countries, such as Jordan, the last time people were asked about their security of tenure was 25 years ago (Razzaz, 1994). Prindex's efforts offer an overdue refreshment of data collection activity in many countries but, above all, it collects data in different parts of the world at the same time. It also satisfies growing efforts to collect data on perceptions of tenure security (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Number of studies finding quantitative evidence of perceived tenure security by year

Consistency of when and how people are surveyed about their perceived tenure security, and who is asked, is therefore key. We have only covered three of the main issues that social scientists face in measuring perceptions, but there are many more. For instance, whether the question is placed towards the beginning or end of a survey, or how the question is translated into local languages. But with every one of these issues the solution is the same: to combine rigorous methodology with a consistent approach.

[1] The detailed results, including all citations, will be presented in a forthcoming peer-reviewed article.

[2] There are other differences between the two studies that may account for the difference. For instance, Stickler et al.’s (2018) study is limited to three counties whereas the Prindex survey is nationally representative.

[3] At the same time, the concept of something being “likely” may also vary across cultures. However, we do not consider it as volatile as concepts of worry or fear.